I sat beside a cairn atop Chandrashila watching clouds rise. Freezing in Sujaan's choti at Tunganath, a combination of sleep deprivation and oxygen depletion had effectively ruled out my much cherished ambition of making it to the peak before sunrise that day. Feeling a little better as the day wore on, I decided to make a try for it. After all, it was a beautiful sunny day.

At Tunganath, the weather changes every ten minutes. This a local saying, and absolutely true. I definitely didn't want to tempt the weather while the sun was still shining. So I told Biru to wait a bit for Sujoy and Debo- the friends I was travelling with- to wake up and struck off on my own. I had last climbed it in May this year. I was way fitter then, so I had very little hopes of making it up there without huffing and puffing my lungs out. As it turned out, the mountain paid me a huge compliment. Probably because I was a lot better used to breathing on this altitude, even with stops to make calls to people (high up the peak I was getting a signal from Gopeshwar on the other side of Chandrashila!) and admire the scenery, I still managed to get up there in half an hour. I was about to ring the bell at the tiny temple of the moon, when I happened to look beyond, and time literally stood still. Far away, yet strangely near, on the North Eastern horizon rose a gaggle of sharp peaks.

Pic: Nanda Devi and her sisters hold court on the far horizon

Two I could immediately recognise because of their distinctive shapes- the mighty Nanda Devi, and Hathi Parbat, the presiding peak of the Bhyundar Valley.

The temple was forgotten. Mindful of the fact that soon either my camera's going to freeze or that the batteries are going to give up, I quickly took as many snaps of this magnificent scene as I could. In the not-quite-noonday sun, the distant white peaks look like translucent chalk sketches against a blue 3D sky. Needless to say, it was unlike anything I'd ever seen before, except maybe in some dream.

The immediate patch of rocky ground behind the temple (the highest point on the peak) is covered with cairns. These vertical structures of various sizes are made from slabs of stoes from the peak and seem to be constantly made and re-made. In May I had asked Biru what these structures signify and he'd said that these were memorial stones. To my fevered imagination they look more like portals into some other world. Amongst them, a Japanese man was singing.

It was a surreal sight. This middle aged man had planted his walking stick upright, slung his thick ski jacket and hat over it, and was lying in its shade reading a book, and occasionally breaking out into song. He grinned at me and went back to reading and singing.

Pic: A Japanese sun-worshipper on Chandrashila

A few feet from him, at another part of the peak behind some other cairns, another of his compatriots was sitting still in a lotus position with his face towards Nanda Devi, deep in meditation. In all there were three of them. I was to bump into them over the next few days, either meditating on tatami mats on the peak, or wandering about wearing a lost look in Tunganath, where they were staying at a different choti.

Making sure that I wasn't disturbing them, I plonked myself down on a rock face overlooking a deep precipice. Down below, through the haze and rising wisps of clouds I could see the wooded valley that had so caught my fancy the last time I was here. In front of me, still visible clearly, rose the distant panorama.

It felt just so exhilarating to finally see Nanda Devi, unencumbered, in all her glory. The other time I'd seen her, it wasn't this sideways view. Rather I'd seen her head on, part veiled by the Mai ki Toli ridge, but with both her twin peaks visible. This was from the Binsar sanctuary in the Almora hills of Kumaon, from where its much closer. From the peak though, she looked serene, detached from the dramatic, wild beauty of her environs. Its easy to see why people revere her so.

But my view of her and the other distant giants depended purely on the whim of the clouds. By nine thirty, the day's heat had had its effect on the sub-tropical climate in the valleys which were giving rise to a succession of little pillow like clouds. While many dissolved in the cooler air above, many more started to form little gangs, which then became bigger gangs.

Pic: Cloud-eye view

Clouds change shape better than any con artist. Constantly forming, disintegrating, reforming, flowing into, out of, over and around ridges, they form an elaborately graceful ballet of carefully choreographed chaos. And so they roamed about me, avoiding this high peak, but erecting and dismantling teasing curtains between me and the distant peaks. So every now and then, all evidence of the far vistas would vanish, leaving me to wonder at what I'd seen. The first time Nanda Devi was cloaked, two Monal took wing, circling overhead while uttering mournful cries, as if in her memory. Then there were the giant Himalayan Gryphons, their backs glinting in the sun, gliding from one air current to another, circling the upper air. They seem totally at home, yet impervious to the beauty of the place.

Pic: Massive Himalayan Gryphon flying high

As the sun climbed higher, the ever present buzzing of large , laggardly flies increased. I'm absolutely not well informed on insects, but the sheer variety I saw on this lonely peak was breathtaking. And then there were ravens. Massive black birds, graver and more ominous than your average crow. They seemed to be constantly watching, flying from one impossible rock overhang to another, squawking, and making these strange half conversational sounds. They are mysterious birds, who indeed hold parliaments when there is a quorum. I can't think of a more appropriate word to describe a group of these birds.

When there was nothing to see, I simply closed my eyes. Immediately my ears pricked up. The wind blowing; a sensation of cool moisture on my cheeks; rustling, buzzing insects; an occasional avian cry. But above all, silence. Every now and then, a sound from a distant village, many thousands of feet below. Startling and funny, like rocks talking to each other.

After a spell, I opened my eyes, and the clouds had shifted. I could see Nanda Devi and her sisters holding court again in the bright sunshine. To my right, above the great green valley that leads to the Anusuya Devi temple in the jungle, huge plumes of clouds were forming. In front of me, due north, Neelkanth was suddenly revealed in all her glory. Further North East small tufts of clouds hung in the air between Chandrashila and the Kedar Massif, casting little shadows on the rich bugyals (high altitude meadows) below the range. At moments like these, I stared in vain at my notebook, struggling to find words evocative enough to describe this beauty. I smiled to myself, imagining the poet Coleridge on this peak, startled out of his opium haze into a fresh appreciation of the sublime. He was a staunch lover of mountains, sometimes recklessly so. One one occasion, he managed to get himself trapped in an impassable grotto in the Lake District. With dusk coming on, and risking exposure, he decided to shut his eyes, take a deep breath and will his way out of there. Opening them, he realised that there indeed was a way- through a difficult and dangerous rock scramble. Sure enough he did. A fascinating story. My guess is, he'd have loved this place.

Bang in front of me, between Chandrashila and Neelkanth, rose a bleak naked rocky ridge, which the local people refer to as kala paththar. An evocative enough name. Back in May, it was covered in snow and ice, but now there were just rocks, and the occasional huge gash signifying the path of a winter snow-field. But it says something about the enormity of the geography here that these same locals believe that there's nothing there. Wrong. Behind and beyond that ridge lies Nandi Kund, an enormous lake from which rises the Madhyamaheshwar Ganga, as well as the huge green hanging valley of Pandosera. That way lies a high track that crosses a couple of high passes under the toe of mighty Chaukhamba to gain access to the Bansi Narayan temple on a massive ridge further to the East overlooking the Alakananda Valley. According to Biru, many sheep-herders often go that way, as do other local people to collect Bramhakamals or the huge lotuses that the high Himalayas are famous for. Someday I'll get to see the place, I hope.

Pic: The forested river valley below Chandrashila, with a snow covered Kala Paththar in the background.

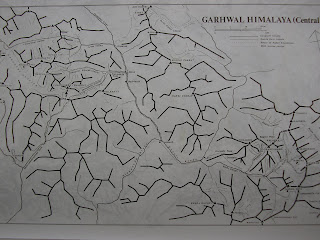

Chandrashila is the highest peak on a long, high and incredibly serrated ridge that runs south to north from the forested valley of Chopta to the highlands below Chaukhamba, running parallel to the Sari and Madhyamaheshwar ridges. Some of the other high ridge-points that I'd been climbing over the last few days with Biru now lay below me- awesome mountains in their own right, but somehow dwarfed by their magnificent setting. As I gazed, some ravens took wing, circling lazily in the morning haze.

Through all the shifting weather, the four white pillars of Chaukhamba rose imperiously, as if above human concerns, glinting severely yet reassuring in the sun. To think that just behind its massive ramparts lay the Gangotri glacier and all those fabled peaks.

Pic: Chaukhamba

Some of them I could see from there- Thalay Sagar and Shivling, beautiful spires both, are visible slightly behind the Kedar Massif. Then come the peaks of Meru, Mandani, the Bhagirathi group. Many peaks, of which I am not sure of the names. In those fabled lands had travelled both my heroes- Eric Shipton and Umaprasad Mukherjee. Both had also come here. In his journal on the 1934 Nanda Devi expedition and the subsequest crossing of the Kedar-Badri watershed under Chaukhamba, Shipton wrote about a zig-zag high altitude pass he took to get to Chamoli back on the way to Joshimath on the road to Badrinath. There it is below me, rushing down the eastern face of Chandrashila on its way down to the forests of Mandal to join the motorable road to Gopeshwar and Chamoli.

Pic: The old pilgrim trail

Mukherjee made special mention of this pass, extolling its natural beauty and bemoaning the unwillingness of pilgrims to take this harder but more enjoyable old route just because there was a tarmac road passing below through Chopta. He was writing in the early 60s. Now, it has fallen even more into disuse. While in the dry cold weather of May, I could easily make out the contours of the path, now in verdant October, just a memory of the path existed. Mukherjee was a deeply religious man, but even he acknowledged that the true reward of making the long and arduous climb to Chandrashila was this view of the high peaks. Amen.

This land is so old. It fills you with a deep awe that's beyond simple religiosity. As I sat in that private paradise of mine, I prayed that I'd never forget it.

Pic: Two views of Lipu-Lekh pass; (above) the southern face, India and (below) the northern face, Tibet

Pic: Two views of Lipu-Lekh pass; (above) the southern face, India and (below) the northern face, Tibet